Teaching for Inferring

Aiden and his older brother, Jack, sit together to eat. Aiden lifts his banana, it slides from his fingers and drops to the concrete. Jack quickly comments, “Better eat that now; don’t save it for later.”

“Why?” asks Aiden.

“The bruise will make it go brown and squishy. Then it won’t be as good to eat.”

“How do you know?” enquires Aiden.

“I’ve dropped apples before. Trust me.”

Why does Jack think the banana will spoil? And why doesn’t Aiden?

Jack’s prior knowledge and experiences about apples have assisted him to make an inference about Aiden’s banana. Without prior knowledge and experiences to draw from, it is more difficult for Aiden to make the inference.

So, what makes inferring so tricky for so many students?

- Could it be an absence of prior knowledge from which to draw?

- Could it be an inability to locate evidence to support inferences?

- Could it be a lack of understanding about what a question means or what a questioner wants?

- Could it be a lack of knowledge about what inferring is and what it involves?

All of these factors make it difficult and sometimes impossible to interpret, or infer meaning.

If we observe students finding it difficult to interpret or infer, what do we do next? As educators, we make teaching judgments based around these observations. We plan for specific instruction, seeking out materials or resources which suit the teaching purpose and which are relevant to students. We select a teaching approach, or mode of delivery, which best supports learners to acquire knowledge, shifting the degree of support as needed in order to facilitate the most effective learning.

As with all comprehension skills and strategies, inferring is a life skill. It serves one well within the context of classroom reading, listening and viewing, but also in life in general. Being good at reading people, situations and circumstances is greatly advantageous. This creates boundless opportunities for teaching and learning and sets a clear purpose for developing high level of proficiency.

So what’s involved in teaching inferring?

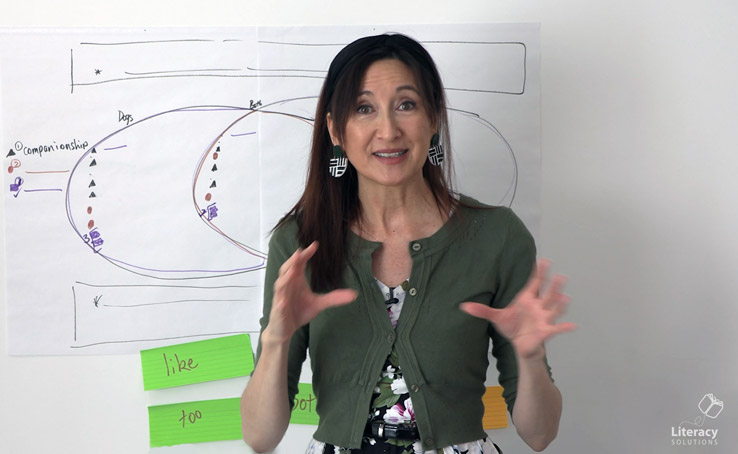

We draw on prior knowledge, or everything we know or have experienced and combine this with knowledge of the text. By finding evidence in the text and applying prior knowledge, we are able to “read more” into the situation than may have been directly communicated.

To teach students how to infer, it is helpful to model, or demonstrate, the thinking which occurs.

In a modelled or shared lesson, the teacher states the lesson goal. For example, Today I am going to use what I know, my prior knowledge, in addition to (visible) evidence in the text, to infer, or make assumptions about what may be going on.

Example:

Students are shown a photograph of a crying child, knee scraped, exiting the soccer field.

- “I see that the boy is wearing the same uniform as the players in this team, so I can infer he belongs to this team.” (points to players in same uniform)

- “From their positions on the field and the way they are facing, I can infer that this boy’s goal is probably this one.” (points to goal)

- “The bleeding knee leads me to think that this boy may have fallen or tripped.”

- “Based on what I know of these types of injuries, I can infer that the injury probably hurts. I can also infer that if this boy applies pressure to this wound, that it should stop bleeding.”

- “From the spectators’ clothing, I can infer that it is cold.”

- Etc.

To check an inference, encourage students to reflect by using a variety of prompts:

- “Does my thinking make sense based on the evidence in the text?”

- “Based on the evidence, is my inference likely?”

- “Is what I am thinking probable?”

- “Is my inference logical, given the circumstance?”

- “Could/would that be possible?”

- “What is the author trying to say to me?”

- “What is it that the author really wants me to understand?”

- “What conclusion can I draw, given what I know and what has been said?”

- “What can be deduced from this?”

- “A likely assumption is …”

- “I could assume that …”

- “Based on …, I can assume …”

Opportunities for teaching are limitless. A wide variety of texts and text types across all subject areas provides great scope for frequent lessons and focused interactions around inferring.

We have developed two new workshops on inferencing in Years 1 and 2 and inferencing in years 3 and 4 which provide teachers with a variety of practical lesson ideas for teaching and provide strategies which support students to make and validate their inferences.

Hi Angela

The opportunities for teaching inferential comprehension present themselves in many ways throughout the week. However, the idea to put up a stimulus (picture or text) as we are marking the roll each day is fantastic. After explicitly modelling how to infer (using a T chart seems to work really well)the students can then hone their skills daily. Sharing ideas in particular seems to help students with the concept of inferring.

It is so important to model thinking and reasoning for students, and not just once!

The points made about prior experience support my opinion on expecting young students to write “Stories”. Children who don’t read or who are not read to have little prior knowledge to draw on.

This lack of prior knowledge even effects the way they attack problem solving in Mathematics, and not just in the lower grades.

e.g. One problem was about a farmer packing “cases of fruit”. My student couldn’t understand why he would want to take a case of fruit on an aeroplane.

So simple, but no doubt I’ll find these strategies quite effective. Thanks

Wonderful ideas. I really like to use a framework which focuses on characters’ actions, speech and appearance to help students draw conclusions. Reading across the curriculum allows for opportunity to explore inference in texts. The prompts are great and require students to familiarise themselves with the vocabulary used.

A useful set of types of questions to ask to get students thinking

very useful

A simple idea yet very effective. This has worked well with my class to help them draw conclusions.